My apologies for the long lapse between writing essays. If I’m honest, the world has been just too much to afford me the mental space to think, write, edit and record these essays. I’ve taken on more responsibilities and simultaneously fell down the rabbit hole with the US presidential elections. And, despite not being directly affected by the ousting of the “Great Orange Liar”, I can’t help but be touched on a personal level. Seeing the once-great nation disintegrating in front of my eyes bothers me much. That’s all I’ll say for the moment.

On a more positive note, as we draw ever-closer to deploying what might be a solution to our number one problem of the novel coronavirus, I thought I’d take a look at what the pandemic has exposed and what digital transformation means today.

One last note on housekeeping, the keen-eyed will notice that I have moved this newsletter to my companies’ domain (dgtlfutures.com). Everything else stays the same and all the existing links still work. It is now easier to find, as it is at newsletter.dgtlfutures.com

The state of Digital Transformation in 2020

When the pandemic appeared to be a real threat to the countries in which it took hold, many including myself estimated that this might be the impetus required to get companies to start, deploy and finish their digital transformations. The reality couldn’t be further from the truth, and it comes back to some difficulties I’ve been discussing for years.

Let’s take a look at where we are in digital transformation today. I’ll go on to show what is missing, what is needed and how we get there.

The first wave - The implementation of computerised back-end systems

The likes of IBM with their AS/400 and DEC with their VAX minis and mainframes were the masters of this. Not because it was hard, but because it was easy and it was a licence to print money. Ever since the first VisiCalc spreadsheet showed the CEO that he or she didn’t need to manually calculate the columns and rows themselves (or have one of the minions to do it), it was inevitable that computerised system would penetrate deeper and deeper in businesses. Those that afforded the outrageous costs of the time, were given an advantage that had not been seen since the invention of the wheel (the innovation that disrupted the movement of atoms from one place to another).

Quickly, IBM and their competitors spun up massive sales teams that crisscrossed the globe demonstrating and selling stock control systems, basic accounting ledgers and simple statistical reporting programs. On the back of this, software-focused companies ramped up work producing ever more complex designs that piggy-backed on the already-deployed hardware. Being that the business model of the IBMs and DECs of the era was to sell high-margin hardware and lucrative support contracts for that hardware, they were pleased to let the software houses integrate their software as it made the hardware even more desirable.

This symbiotic relationship even gave rise to the “Killer App” moniker we use today.

The businesses that needed to make ever-quicker decisions wrote practically open cheques to the manufacturers, as they were confident that the returns on the investments would outdo the spend. And they were right to believe this, as the entire industry structured itself to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

A long time ago, I interviewed for a support role in one of the world’s largest banks, in their London office. I was applying for a position as a support engineer that would be dispatched to the trading floor. I was genuinely intrigued by the floor and asked if it would be possible to see the environment in which I would be working. After a short pause, the IT manager agreed to the unusual request and led me down the stairs to the big oak doors that displayed an ominous sign on a big brass plate. “Do Not Feed The Animals” it read. I chuckled and braced myself for the spectacle that was a Trading Floor in the early 90s. I’ll tell that story another day. But what I most remember was that each trader had two complete AS/400 systems under their desks. This, a room with perhaps 60 to 100 people in it.

That would be a multi-million pound budget by today's rates. But this was standard issue, as the opportunity cost was so high for traders that were just that slightly slower than their competition during trading hours. Their killer app was the trading platform that operated on super-slim timing to augment the trader’s abilities.

The second wave - The paperless office

After the fury of this first wave of digital transformation, it was clear to businesses that they needed to go further, and hunting season was declared on paper—a hunting season that has not, by any stretch of the imagination, finished yet even in 2020.

But that is beside the point.

End-user facing documents and reports were the next low-hanging fruit, and businesses proceeded to digitise these objects as and when they could based on the technologies at their disposal. Very few companies bought software with the sole intention of moving paper reports to digital versions of themselves. It was just the icing on the cake for most. So now, timesheets, TP reports (see Office Space) and countless other document types were converted.

Operators would export data from the ERP systems like SAP, import them into Excel and produce the charts that ended up in Word and PowerPoint documents. But even at this stage, paper wasn’t entirely eliminated, as often these reports (and I see this still today) were printed out in colour and distributed manually or by mail (the physical internal and external postal systems) for analysis and treatment. At some point, people realised that this could be made more efficient. With the advent of internal email systems gaining popularity, sending the PPT over email was the method of choice that enabled faster and better “collaboration”.

I used the quotes, as, by today’s standards, this could be nothing but further from the truth of what collaboration is. The back-and-forth of individually saved and edited documents on the network led to an exponential growth in data storage needs for both the email systems and the personal data storage systems.

When working on sophisticated archiving systems, I discovered that it was not that uncommon to have approximately 100 copies of the same documents on the network. That email sent to 20 colleagues, saved on their “personal space” produces in one step 41 copies!

The third wave - The age of collaboration

When the apparent limitations of this model became apparent, and the software had caught up, we started to build-out specific collaboration software to address these limitations.

As a side note, it must be said that IBM was (not for the first time) way ahead of this curve. Whilst the likes of Novell and Microsoft were supplying the pipes to connect businesses with unstable and simplistic networking hardware, IBM bought and extended a company that built a virtually limitless collaboration system that was too much too early. Lotus Domino was the first “proper” collaboration tool that let business easily deploy just-what-was-needed software to decision-makers. It included storage, sharing, app-building and elementary database capabilities that were far ahead of the curve at the time. Its complexity and frankly, the hostile user interface was part of its downfall, but it was an essential step in the computing-business interface building world.

Fast-forward to pre-pandemic, and the state of collaboration today. We see that companies that had implemented the new generation of basic collaboration systems could provide some semblance of business continuity. Whilst those who hadn’t yet taken the steps, scrambled to implement tools, shoehorning them into day-to-day operations. With varying degrees of success, it should be noted. The pandemic has forced many companies to evaluate if the tools work. They work that is for sure, and work surprisingly well, as they are developed from years of research and experience testing. Forcing them on to unprepared staff will only expose the frailty of your operations if you don’t do the hard work of real digital transformation.

But back to the pandemic. Businesses that have been forced to close their doors to receiving public in their offices and shops have turned to their most pressing problem of managing the customer relationship. How do I sell to someone who would previously wander around my shop for 15 minutes before picking an item and purchasing it?

Facebook and WhatsApp, for example, have provided a means to interact with the client, and possibly vehicle some sales. I’d argue that those sales were probably not lost in the first place, but let’s not split hairs. However, they don’t address the fundamental problems of a wholesale shift in the customer journey fro discovery to purchase and beyond. Plasters on broken leg might make you feel a little better, but they don’t repair the break! So, as we progress in the pandemic, most are preoccupied with the customer-facing elements, ignoring the opportunity to implement real change that would set them up for the afterworld.

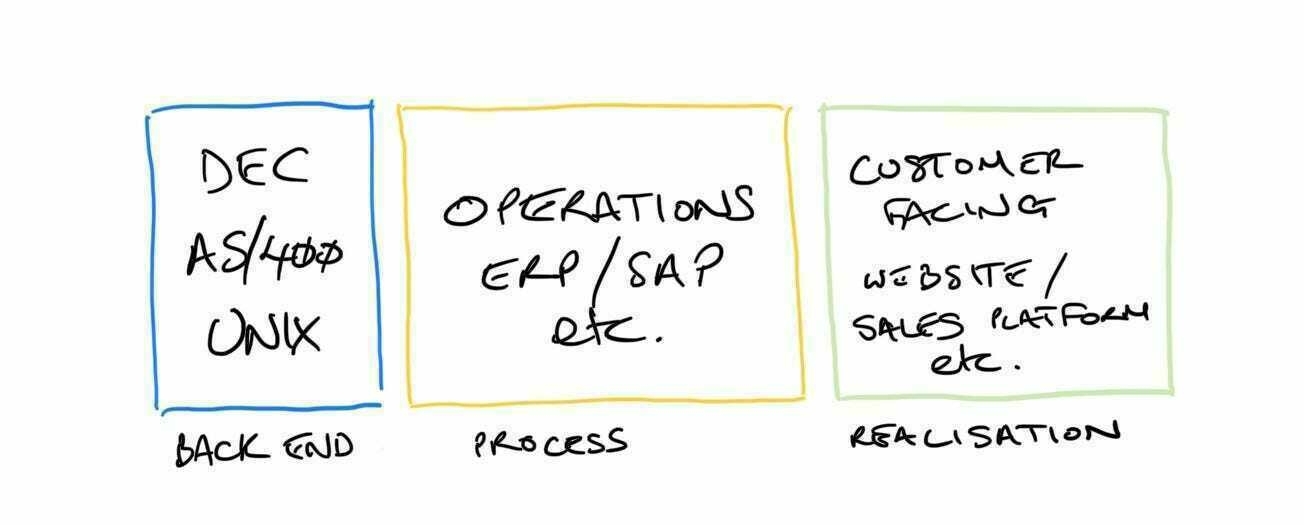

In trying to schematise the idea, I’ve settled on three blocks; the back-end, the operations and the customer-facing parts.

Source: Matthew Cowen

The back-end has been deployed for many years and is efficient at what it does. What is doesn’t do is the problem we have today, however. Legacy AS/400 and DEC systems are still prevalent all around the world. Those legacy systems are notoriously difficult to interface with, notoriously poor at real-time and notoriously poor at providing reusable data for business intelligence, or BI.

But the customer-facing elements are the new centre of focus. It doesn’t take much work to find hundreds and hundreds of businesses that increase your visibility online and help to market and promote your wares, and that’s just in our region. If you think about Internet assumptions, each one of these businesses competes with the millions around the world that are providing the same thing. It’s the reality of the Internet. But let’s not get hung up on that, and focus on the value-added service they’re providing in a world where it increasingly more challenging to be found. This value-add is only limited in that it doesn’t interface well with the real issue for businesses tackling digital transformation, the operations and the back-end. You can sell online, great, but how does that affect the whole value-chain and all the interlacing parts in your business?

The fourth wave (we’re not here yet) - Reimagining the value chain

The elephant in the room is that big block in the middle; Operations. Real digital transformation comes from looking at the whole can of worms that make up your daily operations. The simple tasks, right up to the complex multi-layer, multi-purpose and multi-approval workflows.

I’m not diminishing the value of the fire-fighting going on today in any way — it is a case of survival in many instances—, but the real work should start now. Businesses need to evaluate in detail every single process that makes up their very existence. In assessing, they need to determine three things; 1) the reason a process exists: is it there simply because that’s the way it has always been done? 2) the worth of the process, or to put it another way: what value does that process bring to the business? And 3) the justification for the process: which is not the reason, nor the individual value, but more of an evaluation about how it fits into the whole. Is the sum of its parts greater than the whole?

Redesigning and redeploying those processes is necessary and the only path to digital transformation that will bear its fruits in the future. It will undoubtedly put in question your back-end and will almost certainly change your front-end. And as hard as it will be, it will likely be the difference between your businesses prosperity or ultimate demise.

Intel’s Disruption Followup

I’ve been studying and writing about the disruption taking place on Intel’s x86 line for several years. I’ve written substantially about it here (here and here) in this newsletter and in unpublished form. I explained why it is hard to spot disruption, even if it is happening in front of us. It becomes doubly hard when we are focused on our businesses staying alive, as so many of us are in this current pandemic:

From Intel’s Pohoiki Beach and Disruption Theory:

The problem with theories like these is that it is pretty much the same problem we have when we discuss human or animal evolution. We find it hard to understand the future direction of the evolutive process in real-time, mostly because it happens so slowly and over many generations. From a retrospective position, we can see what happened, and we can often even, have an informed guess as to why it happened. Reliable prediction, it seems, is just unreachable. With modern digital technologies and the pace with which they evolve, we might be able to see enough into the future to discern and predict outcomes for companies in this new world.

I described the history behind Intel’s disruption:

Intel is a well-run long-established microprocessor design and fabrication company, with a phenomenal marketing arm and deep links to the most important companies in the computing industry. Founded in 1968, a year before AMD, it has run head to head with AMD and in nearly every battle beaten AMD on just about every level that means anything; marketing, price, availability, design, availability, to name a few.

The new entrant in the microprocessor market is known as ARM, or as it was previously known, Advanced RISC Machine and before that Acorn RISC Machine — giving you an idea to its origins, powering Acorn Archimedes personal computers. Founded in Cambridge, UK, in 1990 (22 years after Intel), the processor design was a complete revolution and rethink of classic processor design, with the clue in the companies’ original name; RISC.

RISC means Reduced Instruction Set Computer. The Instruction Set of a processor is a fundamental element to how the processor behaves but more importantly, how it is directed to do things, what is more commonly known as programmed. Modern terms, such as coding are basically the same things. Different microprocessors can have the same instruction set, allowing programmers to write the same code, or for the compilers — software designed to turn more human-readable code into native machine language, that is virtually impossible to understand as a human — to translate into the same instructions.

Compared to ARM, Intel microprocessors are CISC, Complex Instruction Set Computers. Without going in to microprocessor design, an instruction is a type of command run by the processor to achieve a desired outcome, like a multiplication, division, comparison, etc. Complex instructions can be of variable length, take more than one processor cycle to execute (processor cycles govern how fast the microprocessor can operate), but are more efficient in memory (RAM) usage. RISC instructions are more simplified and standardised, and critically, take only one processor cycle to execute. They have trade-offs, managing memory (RAM) less efficiently and require the compilers to do more work when translating the code into machine language, i.e., potentially slower development times whilst waiting for the compilation to finish.

The memory issue was only an issue until recently, when memory has become effectively abundant and cheap, allowing hardware designs to incorporate huge amounts of RAM in their designs.

At the begginingg of my writing, I’d tried to frame it in terms of Clayton Christensen’s Disruption Theory, an observation that was, at that time, not frequently put forward. A recent blog post on Medium by one of Christensen’s students vindicated what I’d been writing about for a long time. Have a read if you’re interested in the theory. He does a great job of articulating it.

But it got me thinking about how one could spot disruption or more importantly, one could use the framework to try to provoke disruption. In this essay, I’m delving into that first point.

How do you spot disruption?

Going back to the basics, and ignoring all the incorrect uses of the word —no, disruption is not just doing the same thing but cheaper— I thought I’d try to give you the tools to see disruption happening in your markets.

The big red flag to look for is a product or service that does some of what your existing product or service does, but does it better on a couple of metrics simple metrics; price, efficiency and friction.

Cheaper is not disruption

A less-expensive product alone is not a sign of disruption. What is, however, is a product that evolves steadily providing more and more features and competing on more and more parts of your product or service all whilst its price is significantly lower than yours. Again, it might just be a cheaper product to produce and sell. You have to ask from the customer’s point of view. Is it fulfilling the job to be done? Is it good enough that it makes your buyers question the need to pay your prices? Can your customers successfully integrate and use the competing product despite its shortcomings over your product and still find value?

Efficiency is key

If the competing product is more efficient, be that in the sales cycle, the use-cycle or the complete lifecycle of the product, buyers will, of course, investigate and evaluate that product. Can the product do essentially the same job as the existing product on the market? Does it do this faster, better with more predictable outcomes? Efficiency might afford you competitor lower costs too.

Friction is proportional to sales

Friction is often overlooked as an important force that influences buying habits. The more you reduce friction in the purchase operation and reception of the product, the more chance the buyer tends to have in choosing your product over a competing one. If the new entrant has substantially reduced this friction compared to the friction required to purchase your product, this should be another indicator that things might be difficult from this point forward for you.

Loyal customers may soften the impact at first, but even the most faithful will switch if the product fulfils several of the criteria I have highlighted above.

But that alone is not enough, you need to have historical data, or you need to develop a way to project into the future and make assumptions about where you think the product and service are going or where it could go. Just look at the image that explains disruptive innovation below. Looking at the “Entrant’s disruptive trajectory” line as compared to the “Mainstream” line shows how, eventually, disruptive innovation will surpass the mainstream product or service when “performance” is evaluated based on the metrics I’ve highlighted above (to name a few).

Source: HBR

If you are the incumbent and you wish to stay profitable and dominant, you have but two choices. Embark on a “sustaining trajectory” or innovate your own disruptive innovation. Just be aware, a sustaining trajectory has its upper limits!

The Future is Digital Newsletter is intended for anyone interested in Digital Technologies and how it affects their business. I’d really appreciate it if you would share it to those in your network.

If this email was forwarded to you, I’d love to see you on board. You can sign up here:

Visit the website to read all the archives.

Thanks for being a supporter, have a great day.